- Adi Thakur

- Jun 30, 2025

- 1 min read

Hello, long time no see,

I am back after an extended, lazy sabbatical, and after a few years of putting this on the backburner, it's time to summon this page back to life.

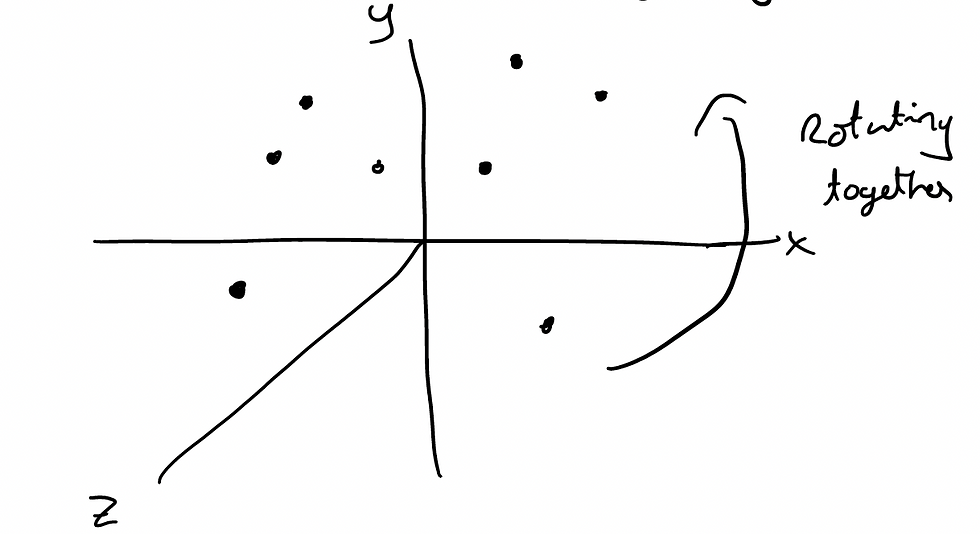

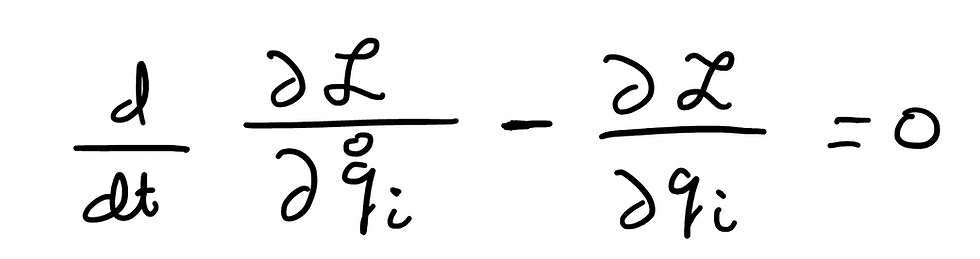

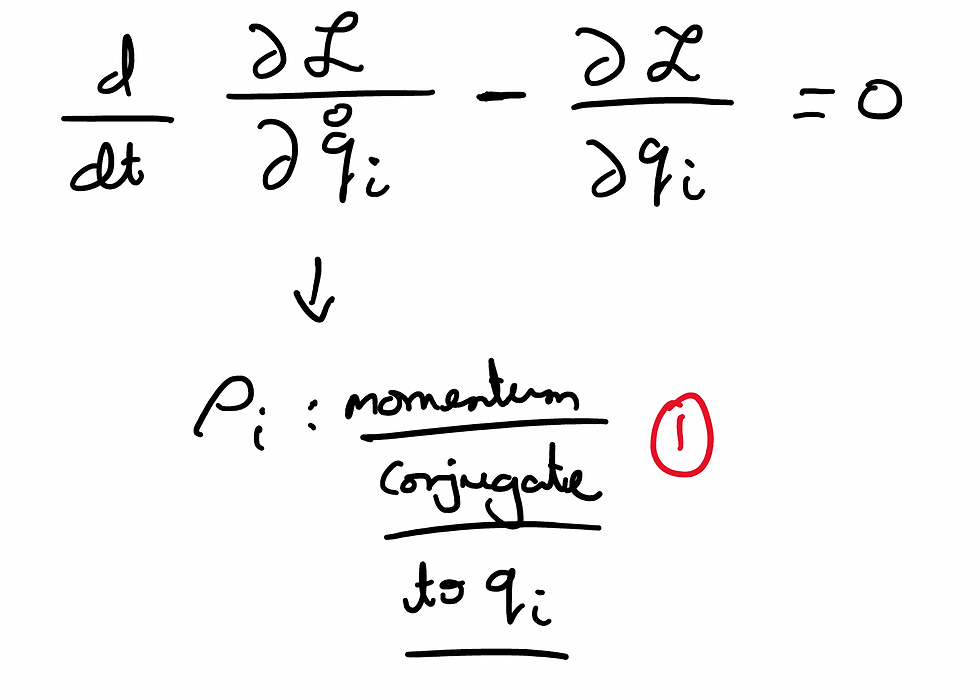

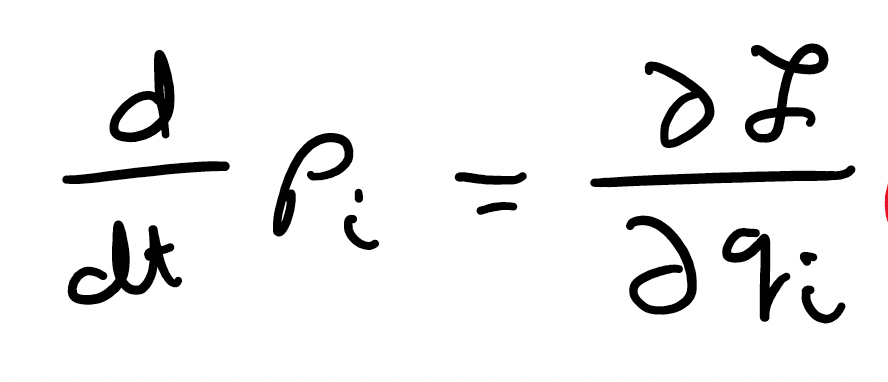

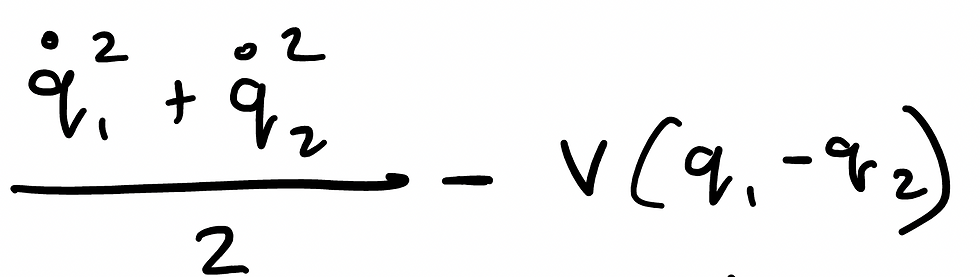

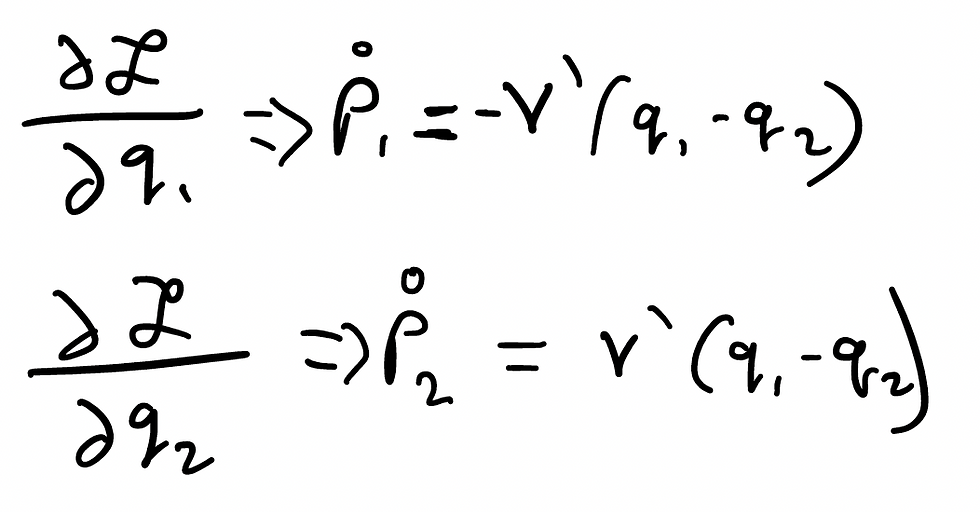

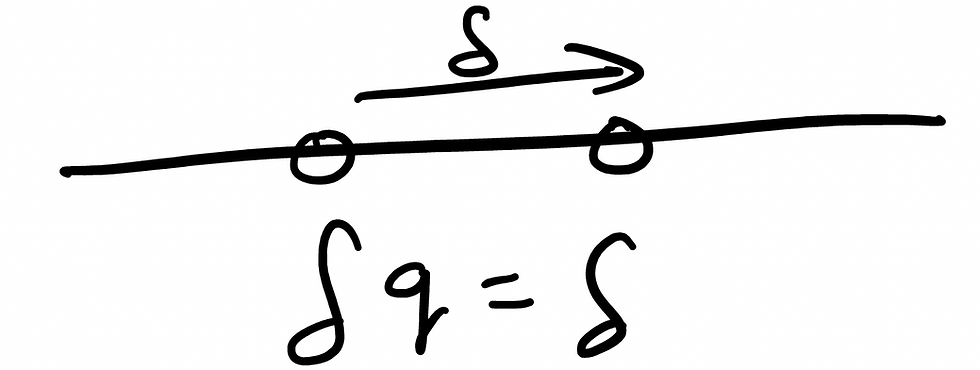

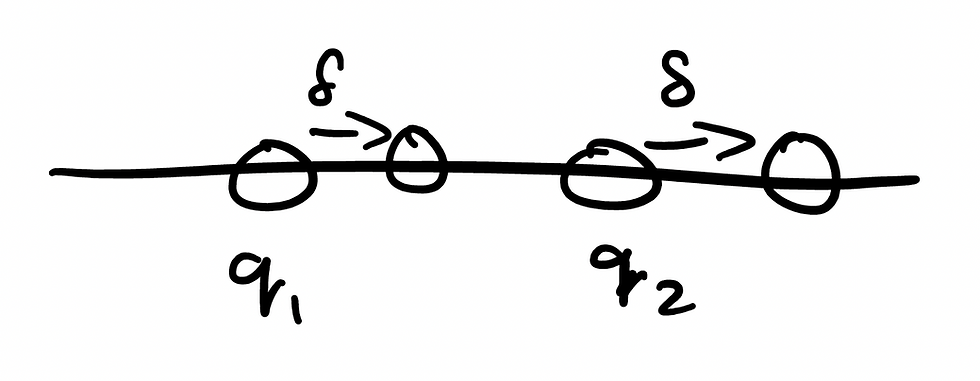

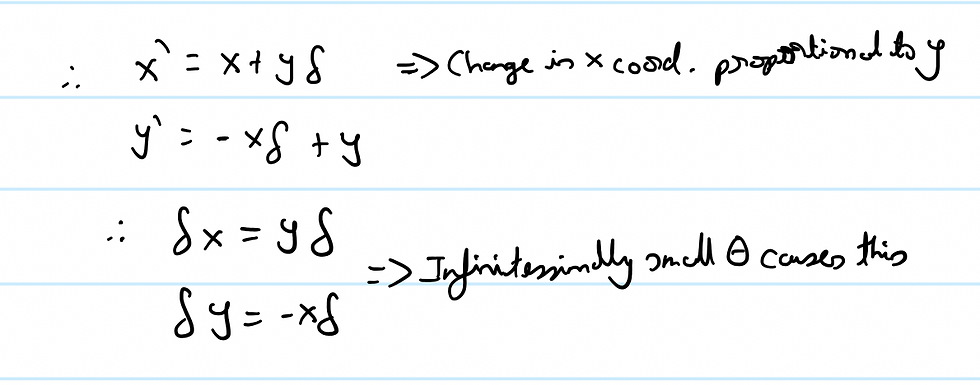

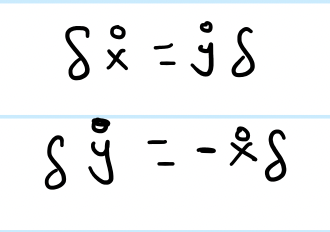

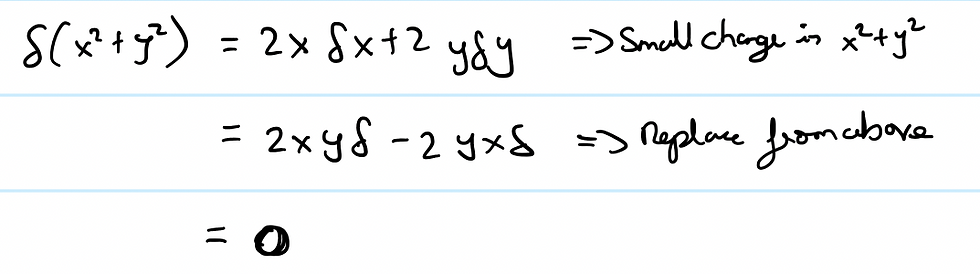

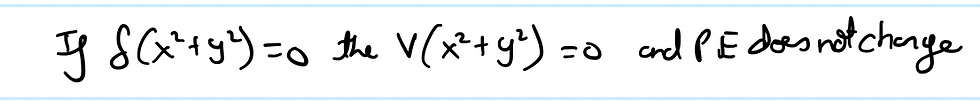

I shall start with some basic notes on the basics of quantum physics, and try to make them even more basic than the basic notes themselves. Just like my coffee order, I will try and make it super basic (if that wasn't already clear).

I'm also keen on sharing some updates from arx.iv. That place is a godsend and I'd love to bring to light some of the newly released papers I find interesting on there.

Let's send this.